Forest biodiversity is protected by conservation and, in commercial forests, by nature management. The goals and methods of nature management are surprisingly similar across Europe: more deadwood, ecological corridors, natural regeneration and protection of birds.

Possibly the most comprehensive report on nature management in European commercial forests is a report published in Switzerland with the title How to balance forestry and biodiversity conservation. A view across Europe.

The authors of the report emphasise overall sustainability. Nature management in commercial forests is important because it strives to ensure not only timber production, but also forest management that is friendly to both humans and the environment. Sustainable timber production is a key field of sustainable economy in Europe. According to the report, Europe should achieve self-sufficiency in forest products.

Europe has at its disposal unique know-how in the nature management of commercial forests. Forest professionals have developed numerous methods of for it: close-to-nature forestry, such as the selective harvesting known as the Plenterwald method, the practice of leaving retention trees, continuous-cover silviculture and reduced-impact logging.

Biodiversity needs to be created

According to the Swiss report, biodiversity must also be actively created by imitating forest damage, one example of which are wildfires. The researchers say that so far, using such methods are not viewed favourably enough by society at large or the forest sector itself.

The widespread damage caused by bark beetles in Central Europe, for example, have increased criticism against resorting to intentional damage. However, the report says that attitudes regarding this are changing.

The report stresses that even if the dominant conflict regarding forestry continues to be that between timber production and biodiversity, there are also other conflicts. More and more often, the protection of biodiversity comes into conflict with climate protection and the recreational use of forests, for example.

The Swiss report divides the goals of nature management in commercial forests into three types: landscape-level goals and goals to safeguard deadwood and the diversity of tree species. In addition to these, the report discusses the social sustainability of forest use.

Nature management methods are compared in a total of 32 sites across Europe. Five of them are production forests in the lowlands and five are production forests in mountainous areas. Fifteen sites represent forests under intensive forest management, four represent forests where the goal is landscape management, and three represent forests managed to achieve a diversity of species.

Six of the sites are located in Germany, and France and Switzerland are represented by three sites each. Two sites are located in each of Poland, Sweden, Scotland, Austria and Spain. Denmark, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Portugal, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Slovakia, Italy, Norway and Belgium are represented by one site each.

On the basis of the Swiss report, we listed the eight most popular methods of managing forest nature in Europe: retention trees and deadwood; structural diversity of forests; natural regeneration; contiguity of forests; uneven-aged silviculture; protection of bird species; increasing the range of tree species and supporting rare tree species; and creating a network of protection sites.

Method 1: Retention trees and deadwood

According to the Swiss report, leaving retention trees is a goal on almost all the sites studied. Leaving retention trees was also one of the first requirements of nature management in the European forest certification systems.

Trees are the most important type of plant in the forest ecosystem. They maintain a diverse ecological network. Removing a tree from the forest means that a great number of other living organisms will disappear.

This being so, it is particularly important to spare large trees in connection with forestry operations. Species which are especially important for biodiversity should not be felled at all.

Trees continue to provide a suitable environment for many species even after dying. A significant number of threatened forest species are dependent on deadwood. They have become threatened because deadwood has been removed.

This is why more living trees should be caused to die and remain upright by such methods as girdling, removing the bark or rind or causing other type of damage. One of the aims of this is to create nesting places for birds that nest in hollows. Standing dead trees and trees fallen in storms, for example, should be left in the forest.

The range of species living on or in deadwood changes as decay progresses. In this way, a dead tree works to maintain biodiversity for a long time after its death.

In Finland, among others, standing deadwood is created by cutting trees at a height of 3–4 metres. These stumps, and the rest of the tree, are left in the forest to create deadwood, being of great significance for many forest species, including many beetles and birds which nest in hollows.

A TV campaign of Forest Finland, the joint communication project of the Finnish forest sector, tells about the forest nature management and and its methods such as retention trees.

Method 2: Structural diversity of forests

A concept used in Nordic forest management is ‘forest mosaic’. This refers to what a forest looks like when seen from high above or on a map. It is a mosaic of different types of vegetation, waterways and wetlands.

Structural forest biodiversity can be achieved by creating a mosaic like this. The Swiss report says that, depending on the overall conditions, the structure may also be improved through environments created by humans, such as forest roads or harvesting stands according to varying principles.

Method 3: Natural regeneration

In order for forestry to be profitable, felled trees should be replaced by new seedlings as soon as possible. The best way to ensure this is silviculture; in other words, sowing or planting a new forest.

In terms of biodiversity this is not always the best solution. Cultivated trees may alter the genetics of the forest and if the forest is hit by a natural or other disaster, they may not survive as well as natural seedlings,

On the other hand, cultivated seedlings, being the result of breeding, will produce better timber more quickly than natural trees.

Especially as regards light-tolerant species, natural regeneration is often better than regeneration by forestry. In Finland, for example, it is known that despite intensive forest cultivation, more than four out of five trees anywhere in the country are the result of natural regeneration.

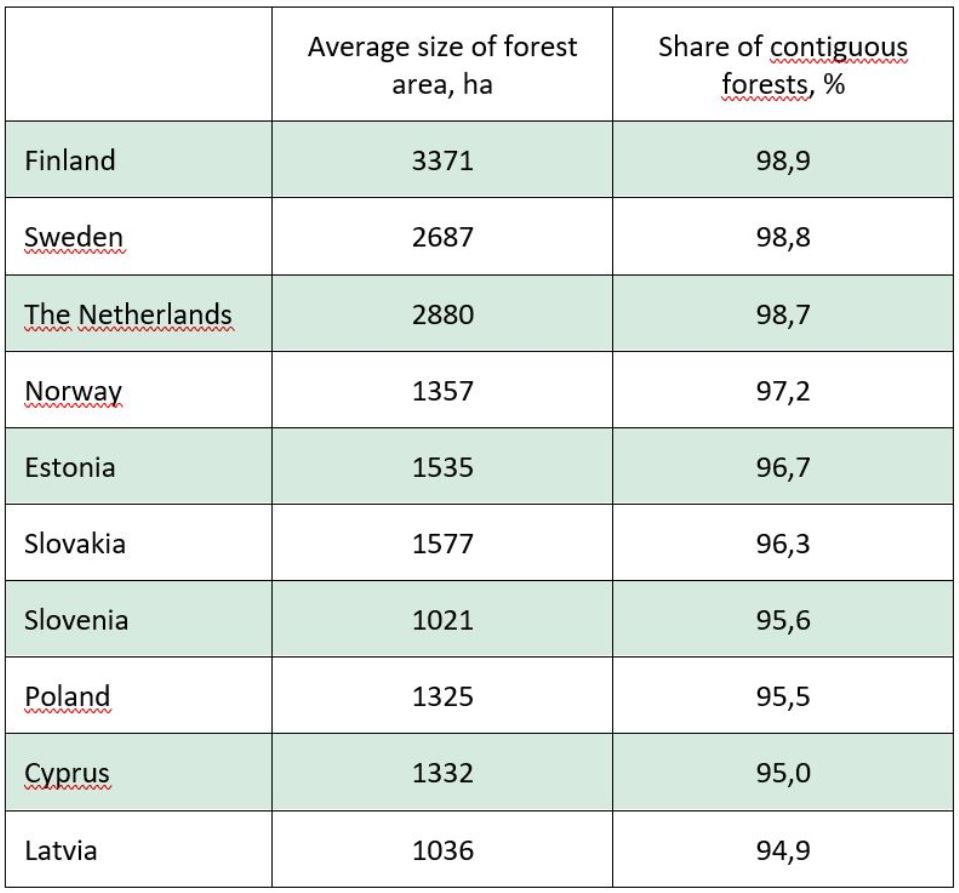

Method 4: Contiguity of forests

It is important to protect valuable forest sites, but this may be less effective if the protection sites are not linked to each other. Every protection site may contain populations of the same threatened species, but if the population is small and isolated from others of the same species, it will gradually weaken genetically.

Eventually that population will disappear in spite of being protected.

To combat this, protection sites should be linked to each other by what are called ecological corridors. According to the Swiss report, good ways to achieve this are protecting small stretches of forest or rare habitats between occurrences of threatened species, or also sparing specimens of valuable trees in forests between protection sites.

Problems caused by the fragmentation of forests can also be solved by inoculation. In Finland, the mycelium of threatened polypores is experimentally transferred to sites where they do not occur naturally, but where they could well live if given the chance.

The existence of contiguous forests in Europe in 2018 – Top Ten

Method 5: Uneven-aged silviculture

Uneven-aged silviculture refers to the existence of trees of different ages in a stand. This can be achieved by selective harvesting that does not change the age structure of the stand.

The alternative is to favour an even-aged stand where all trees are of the same age. In such stands harvesting operations are more efficient, since they produce a large volume of even-aged and -sized trees and there is no need to protect the remaining trees from damage during harvesting.

A completely even-aged forest is no longer a goal even when forestry is based on clear-cutting; at the very least, natural seedlings are protected as far as possible.

Method 6: Protecting bird species

Protecting the vitality of bird species is a very widespread goal of nature management in European forests. In all, 25 of the sites included in the Swiss report seek to improve the vitality of bird species. In contrast, carnivores are supported in just 11 cases and herbivores in 10.

The report makes particular mention of the capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), the black stork (Ciconia nigra) and the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla).

Method 7: Increasing the range of tree species and supporting rare tree species

Trees are arguably the most important group of species in a forest. Each tree species has a specific range of accompanying species. For this reason it is important to safeguard the original tree species in a forest.

Just like other organisms, trees may be threatened for many reasons, and the threat is not always due to humans. Species may also be rare by nature.

The range of tree species is supported by planting, sowing and favouring species which are rare either by nature or due to human activity. The human activities which may endanger tree species include the ubiquitous decrease of forest areas and forestry, which favours certain species, sometimes even non-endemic ones.

In order to safeguard a sufficient variation in the gene pool, seedlings for cultivation and seeds should be gathered in over extensive areas.

Genera mentioned as ones to be specially favoured in the Swiss report are the oak (Quercus), the rowan (Sorbus), the elm (Ulmus) and the alder (Alnus).

Method 8: Creating a network of protection sites

The impact of forest protection is considerably improved if the different protection sites can be designed to form a network and if the sites can further be linked by means of ecological corridors, which is required for achieving the goal of forest contiguity.

Where the protection site is large enough to constitute a landscape. It will be easier than on smaller nature management sites to create within it a dynamics related to natural cycles. This will, of course, be more difficult in countries with few forests.

Read more: Sustainability of Finlands forests

No single, unified indicator for biodiversity exists

The report State of Europe’s Forests 2020 by the Commission of the European Union notes that the nature management of commercial forests is made more difficult by the difficulty of measuring the goal of the activity, that is, biodiversity. There is no single, universally approved indicator or measure, and one must make do with partial truths.

Several countries who submitted information for the Commission report regretted that nature management activity is difficult to implement, even though it is well known what ought to be done. This is an illustration of the conflicts – either actual or imagined – between nature management and other land use.

Setting up extensive protection sites in urban areas has been particularly difficult. One of the reasons is that adopting closer-to-nature methods of forestry is not particularly profitable for the forest owner.

The EU Commission report says, however, that over 105 million hectares of Europe’s forests have been certified, a measure that is voluntary for the forest owner. Certification is most prevalent in areas where the consumers’ awareness of environmental issues is the highest.

According to the State of nature in the EU report by the European Environment Agency, nature management activities do have an impact if only they are implemented. The report says that there are up to 100,000 square kilometres of forest in Europe where the state of nature should be improved.

One comment on “Top eight methods of managing forest biodiversity – Forest nature management has similar goals throughout Europe”

/ Philippe Herman

Heath areas are for me an artificial landscape. I think it is not better to let heath regions – even touristic – evoluate into primary forest?