Decaying wood is important for endangered species. The amount of decaying wood in Finnish forest is increasing, but this does not automatically lead to the return of species that are in danger of vanishing or have vanished from the area. This is where inoculation may help.

The success of reintroducing polypores is studied in a joint project by Natural Resources Institute Finland and the University of Helsinki. The reason behind the research project is the sad fact that over 40 percent of Finnish polypores are endangered, due to lack of suitable decaying wood and of forests with plenty of it.

There are extensive areas in southern Finland where some polypore species have disappeared, in places even completely. The current methods of nature protection do not safeguard them adequately, even though decaying wood is increasing, thanks to storm and drought damage, forest nature management and the increased strict protection of forests.

In principle, habitats suitable for polypores are continuously increasing. The problem is that the red-listed polypores may not be able to access them.

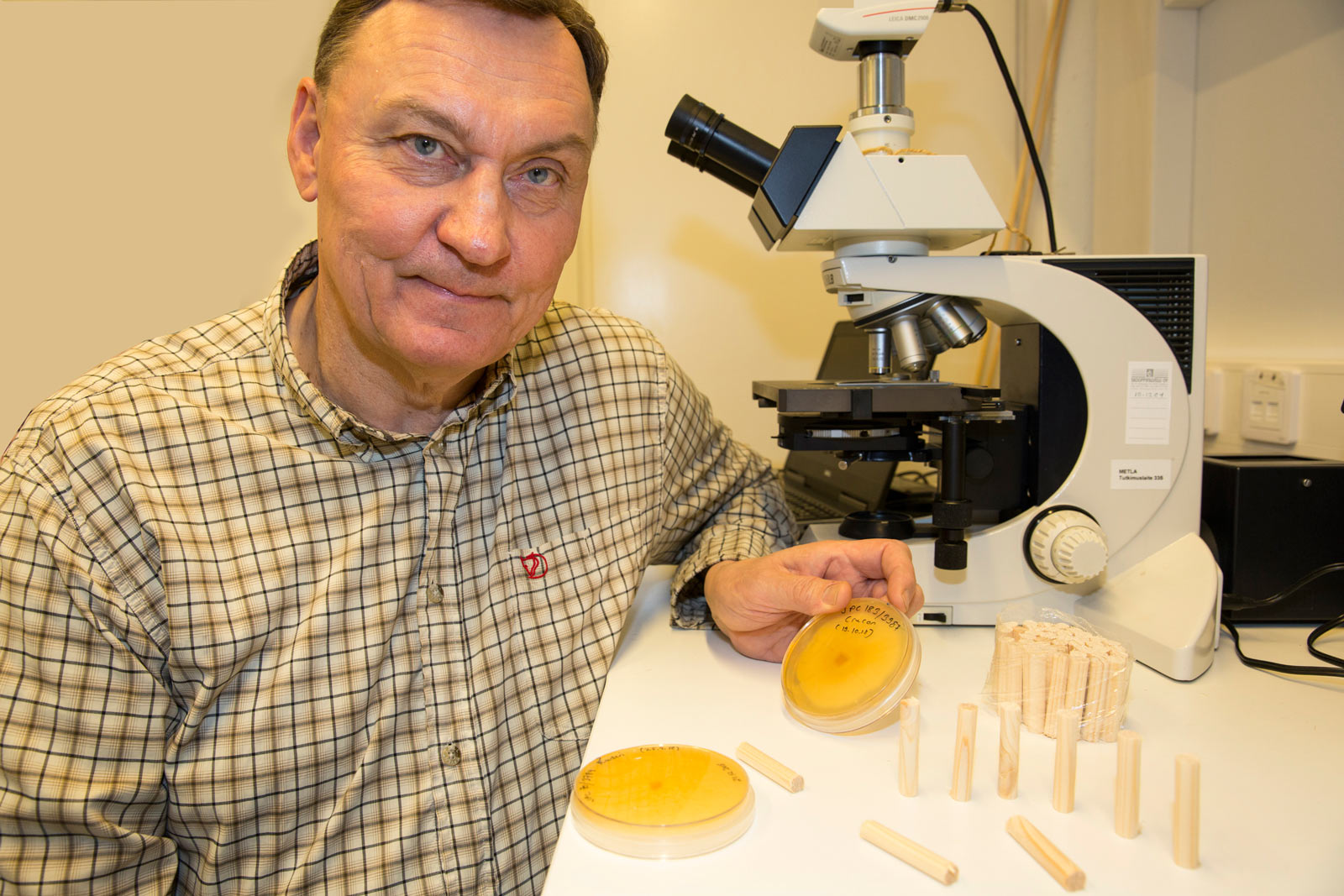

According to Reijo Penttilä, Research Scientist at Natural Resources Institute Finland, one solution could be inoculation. ’The method we are studying enables large-scale inoculation at low cost. We may even be able to commercialise our method,’ says Penttilä.

This is just first aid – decaying wood is also needed

Penttilä stresses that the method can only be regarded as first aid, and its success depends on there being enough decaying wood before the operation. However, inoculation can considerably speed up the emergence of endangered species in the new areas. As regards the most endangered species, inoculation may be the only way to return them to areas where they were previously found.

Polypores are fungi, and transplanting fungi by various methods is nothing new in itself. For instance, transplanting edible mushrooms is common all over the world, and fungi dependent on trees are used to fight harmful fungi, such as root rot.

The transplanting of endangered fungi has previously been researched in a pilot study at the University of Helsinki, with a positive outcome.

All polypores in the project are red-listed

The project, led by Natural Resources Institute Finland, was started in autumn 2018 by gathering the visible fruit bodies of polypores and growing them in a laboratory during the past winter. In the course of this spring and summer, ’inoculation packages’ of the mycelium will be prepared.

These consist of wooden dowels containing mycelium. Next autumn the dowels will be plugged into holes bored in dead tree trunks on the test sites.

The number of polypore species in the study is 22, all of them red-listed. Of them, 12 live on spruce, five on pine and five on broadleaves.

The test sites are chosen from areas where the species studied have not shown up lately. The sites also contain plenty of recently dead wood and preferably also a decay continuum, which means that there is and will be wood at different stages of decay. The continuum will safeguard the survival of the reintroduced species even in the future.

Both trees fallen by themselves and trunks felled for the purpose will be used for inoculation. The Haploporus odorus polypore will also be introduced into living goat willows (Salix caprea).

Ten spots will be selected on one side of a trunk, at intervals of one metre. Three holes will be drilled at each spot, and wooden plugs with mycelium will be pushed in and covered with wax. In addition, the DNA in the dust from the drilling will be analysed to determine what effect the fungus species found naturally in the trunks will have on the success of the species introduced.

A record will also be made of trunk size, stage of decay, presence of bark and epiphytes living on the tree, such as moss and lichen, and the trunks’ contact with the ground.

The inoculation sites will be monitored for five years at least. In the follow-up, the spreading of the introduced mycelium will be determined by drilling dust from the trunks close to the inoculation spots. At the same time, the emergence of fruit bodies will be studied. Five years after the inoculation, only the presence of fruit bodies will be studied.

All in all, inoculations will take place on 15–20 spruce- or pine-dominated forest sites, and on s spruce-dominated site with aspen and goat willow. The sites are owned by the state forest company Metsähallitus, the forest industry company UPM and the City of Helsinki.

Pilot study Reintroduction of threatened fungal species via inoculation