The quality of the best Scots pine butt logs from continuous-cover forests is so high that market demand for it may be non-existent. Evaluating the profitability of growing them is difficult, as this would require information about the market, which does not exist for this grade of wood. Sufficient data on tree growth is also lacking.

In any case, Sauli Valkonen, Senior Scientist at Natural Resources Institute Finland, recommends caution: ”This is an example of extreme results. We have carried out sawing tests in an 180-year-old Scots pine stand in Evo, southern Finland, where the wood quality is practically as high as it can get. Our message is that this is something that can be reached, but probably not always,” says Valkonen.

In addition to an overstorey, the stand contained an advanced understorey, where the breast-height diameter of the trees could be even 30 centimetres.

Seedling felling is a good way to start

The continuous-cover management of Scots pine differs from that of spruce, which is managed by selective fellings or small-diameter clearcuttings. Still, according to Valkonen, it is not difficult.

The change from clearcut-based management of pine to continuous-cover management does not require a transition period. The first step could be a normal seedling felling, where all trees are felled, leaving only large mother trees to provide seeds for the new forest. ”You also have to prepare the soil to some extent to ensure a good start for the new seedlings,” says Valkonen.

Normally the mother trees that are good stout timber are logged as soon as the new stand has got off to a good start. ”However, in this case you should have the patience to leave them standing for a bit longer,” says Valkonen.

The next operation in the forest is thinning, which could take place in 20 years after the start of the new stand. ”At this point you could harvest some of the mother trees left over from the previous overstorey,” says Valkonen.

The harvesting operation must be carried out carefully so as not to damage the young trees. ”But it isn’t much more difficult than normal thinning,” says Riikka Piispanen, Senior Research Scientist at Natural Resources Institute Finland.

Small-scale clearcutting, which is a good method for managing spruce under continuous cover, does not function for pine. ”It leads to similar results as the method we suggest, but it takes more time and is more difficult,” says Valkonen.

The result is very strong wood

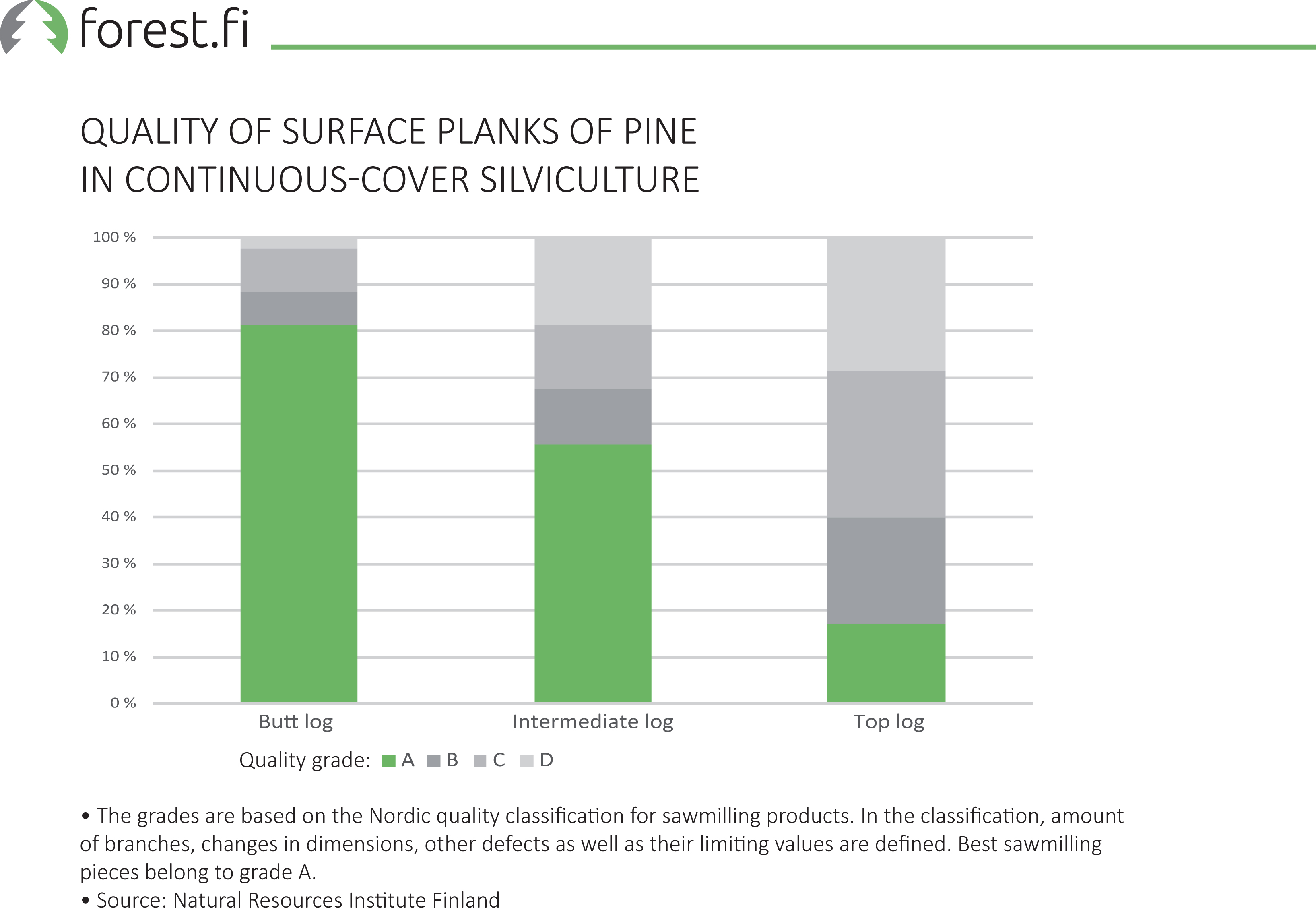

Unlike with spruce, the wood produced by the continuous-cover management of Scots pine is very homogeneous in quality. In addition, the butt logs have no knots even in their outer parts up to a height of 15 metres. There are fewer knots even in the other parts of the wood, and they are smaller than in pines cultivated by traditional methods.

According to Piispanen, this is because of the characteristics of Scots pine. ”Scots pine needs plenty of light. Its branches are situated in whorls, and between the whorls there are no branches. All branches growing in shadow will fall off, so there are branches only towards the top of the trunk,” says Piispanen.

”It is essential to create growth conditions where the annual rings of the inner parts of the log are narrow and there is little poor-quality wood close to the pith;” says Piispanen.

In addition, the logs contain no compression wood, which is denser but weaker than normal wood, and thus they are homogeneous in quality. However, there are reports of compression wood in many studies covering all coniferous tree species. When you lump them all together, you lose sight of the fact that one of the species, that is the Scots pine, does not produce compression wood when cultivated by this method,” says Piispanen.

Pine logs from continuous-cover silviculture are extremely strong. As much as 40 percent of the sawmilling products fall into the top quality grades C35–C50, according to the EN338 standard, actually characterized as ”too good” by the two researchers. 15 percent of the sawmilling products fall into the lower, though still very good, grades C27–C30.

Even these lower grades are not often available on the market of Finnish sawmilling products. The strength was studied using planks with a thickness of 75 millimetres.

Insufficient data to evaluate profitability

Valkonen characterises this continuous-cover method of managing Scots pine as ”surefire”, in terms of regeneration, growth, and generation of quality wood. Even so, evaluating the profitability of the method is very difficult and requires more research. The first problem is that the yield is not known.

One of the results of the method is that large trees shadow the smaller ones, which makes the latter grow more slowly but produce better wood. It is precisely the shadow that creates the homogeneous, high-quality butt logs.

According to Valkonen, the loss in growth of the smaller trees is to some extent compensated for by the better growth of the larger ones. ”Taking only the volume of growth into account, the result may be a little on the negative side,” he says.

Valkonen continues that the growth volume of the larger trees could be around 1–3 percent. ”Though the increase in value may be much larger,” he says.

This, however, is not enough to make the method profitable. You also need to find someone who is willing to pay for the quality.

The profitability is obviously much weaker if you fail to get a higher price for the wood. And this is what makes the evaluation of profitability difficult.

Can willing payers be found?

In the end, the main issue is not the price of the logs, but the final consumers’ willingness to pay more for wood-based products, and how much they are willing to pay. Piispanen thinks that there would be demand even at the higher price – if not in Finland, then abroad.

This is another instance of the chicken and egg problem: to have a market, you need both supply and demand, but which of them comes first and how do you make them meet?

According to Valkonen and Piispanen, there is very little research on continuous-cover silviculture in Finland or elsewhere in the world. ”Take, for example, our studies on the quality of wood. They are absolutely unique,”, says Valkonen.

It is not easy to get funding to study profitability, despite the popularity of continuous-cover silviculture as a topic. Yet the researchers say the work would not require that much.

”We’d need five forest stands to construct the growth models. To include the conditions in northern Finland as well, we would need five more,” says Valkonen.

Previously in forest.fi:

Quality of spruce from uneven-aged forests varies greatly

Continuous cover or not – profitability always depends upon the case