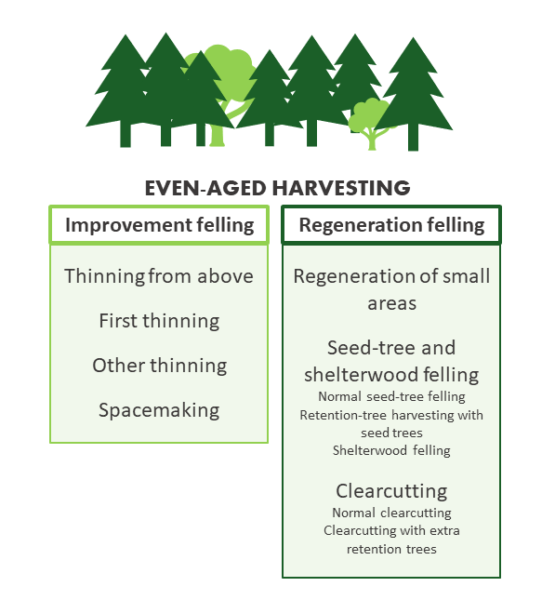

Not just clearcutting – Finnish state forests are harvested by twelve different methods

Good forest management involves choosing a harvesting method that suits the characteristics of the forest compartment and the needs of the forest owner. Clearcutting and continuous-cover harvesting are not the only methods.

In public debate on forestry issues people usually only talk about two harvesting methods, either clearcutting or continuous-cover – or uneven-aged – harvesting.

Uneven-aged forestry does not include a clear stage of forest regeneration. New trees are not planted or sown or the soil prepared in the same way as after regeneration felling.

Among the harvesting methods used by the Finnish state forestry company Metsähallitus, only selective logging and cultivation of small areas are classified as uneven-aged forestry. As the name implies, uneven-aged forestry aims at a forest with a diverse age structure.

On the other hand, forests under even-aged forestry – or periodic forestry relying on clearcutting – also usually contain trees of different ages. A diverse age structure is also the goal of Finnish forest policy.

Even with even-aged forestry it is possible to maintain the forest cover. Examples of methods used here include thinning well-matured stands and removing seed or shelter trees when no longer needed.

New Forest Act introduced continuous-cover silviculture

Periodic forestry is based on forest rotation periods. Each period ends in a regeneration felling, after which the forest is regenerated. This means establishing a new forest stand by planting or sowing new trees or by natural regeneration.

A regeneration felling may be a clearcutting, where all or almost all the trees are removed, or a natural-regeneration felling, where the largest trees are left standing to provide seeds for the next generation.

Up to the entry into force of the new Forest Act in 2014, periodic forestry was almost exclusively the forestry method used in Finland. With the new Act, however, Metsähallitus has adopted continuous-cover silviculture on certain special sites and also in places where it would be difficult to establish a new stand after a clearcutting and the forest is also expected to regenerate naturally.

For example, it may be sensible to avoid clearcutting in hiking areas so as to maintain the recreational value of the forest. In areas important for biodiversity, continuous-cover methods may safeguard special forest fauna and flora and a humid microclimate. The method also helps to create ecological corridors and maintain game management.

Metsähallitus has decided to establish three model areas of continuous-cover silviculture, covering a total of 5,000 hectares. The areas are situated in northern and eastern Finland, and the results of using the method will be monitored for at least 30 years, with reports every five years.

Choice of forestry method should be free

People’s attitudes towards forestry methods tend to have a strong ideological basis: some swear by continuous-cover, others by clearcutting. Timo Pukkala, Professor of Forest Management Planning at the University of Eastern Finland, calls for more leeway in thinking.

The idea of forestry has always been that management methods should be chosen to suit the characteristics of the forest compartment. According to Pukkala, the same should apply when clearcutting is opted for.

In the freestyle forest management proposed by Pukkala one should only look at the current state of the compartment and consider what actions to take in order to meet the forest owner’s future needs. Pukkala thinks the answer is often continuous-cover forestry, but it may also be periodic forestry and thinning or regeneration.

How Metsähallitus harvests

Selective logging may be used in fertile spruce mires and on mineral soils with smaller, healthy trees below the largest trees and a good likelihood of natural regeneration. The method is also good for pine stands on dry heaths, eskers and peatlands carrying naturally uneven-aged forests.

Selective logging can be used in the same compartment at intervals of 10–20 years in southern Finland, while in northern Finland the interval is 15–30 years.

In cultivation of small areas, sites up to 0.3 hectares – that is, half a soccer field – are clearcut. The new stand is expected to spring up from seeds of trees surrounding the clearcut area. To help the seeds to germinate, the soil may also be prepared in connection with harvesting.

Cultivation of small areas is appropriate on sites of the same type as for selective logging, and the frequency of harvesting is also about the same. This method can also be used to begin changing an even-aged forest into an uneven-aged one.

In clearcutting, all or almost all trees in a forest compartment are removed. Retention trees are left on the site according to the forest owner’s wishes or the demands of forest certification.

The PEFC certification, for example, says that ten retention trees per each clearcut hectare must be left. These trees may never be taken out of the forest. Instead, they are allowed to fall down and die to create decaying wood important for biodiversity.

The Finnish Forest Act requires forest owners to establish a new forest stand on a clearcut area within a specified period by planting, sowing or natural regeneration.

Seed-tree felling is a regeneration felling where large, high-quality trees are left standing to provide the seeds for the next tree generation. The method is suitable for tree species requiring plenty of light, such as Scots pine and silver birch.

However, the method only works well when the seed crop is good. Not every year is good, and in northern Finland there may be several bad years in succession. Poor seed years are a problem with all forestry methods based on natural regeneration.

Strip harvesting is also sometimes regarded as a specific method. This involves clearcutting narrow strips of forest, followed by natural regeneration by surrounding trees.

Thinning from above means removing the largest trees. They are often the seed trees left unfelled in seed-tree felling. The purpose of this operation is to allow the remaining trees to grow without being overshadowed.

Thinning from above may form one stage in what is called two-stage forest management, which maintains a continuous forest cover. It starts with a seed-tree felling or shelterwood felling, where the largest trees are left unfelled to provide seeds for the regeneration area.

The trees are left standing until the new generation reaches the height of 1.5 metres. After that, the largest trees may be removed in one or two stages.

Retention-tree harvesting with seed trees is a seed-tree felling where not only seed trees, but also a number of extra retention trees are left standing. According to the Metsähallitus guideline, the volume to be left is either a minimum of 20 cubic metres per hectare or a minimum area of 15 percent of the total harvesting area.

After the new tree generation is well established, the seed trees are removed, but the retention trees are left standing.

Shelterwood felling is a regeneration felling aiming at a natural regeneration of spruce. The largest trees are left unfelled to shelter the young stand of spruce from strong light, because spruce thrives best in shade. Before a shelterwood felling, a thinning of the larger trees may be carried out to enhance natural germination and to strengthen the trees against wind.

A first thinning is carried out when the forest stand has reached the height of 12–16 metres after regeneration. In southern Finland this usually takes 25–30 years, and in the north 30–40 years.

The first thinning is carried out before the competition between individual trees begins to restrict the width of their canopies. If it is left too late, the trees start to lose their leaves or needles and branches, which weakens their growth.

The first thinning accelerates the growth of the remaining trees and allows them to grow stouter. The timber yield from a first thinning can be sold to a pulp mill and may be 30–60 cubic metres per hectare.

As the forest continues to grow, 1–2 other thinnings will be carried out during the rotation period. High or low thinning or quality thinning aim at producing stouter trees and increasing timber revenues.

Low thinning removes smaller trees in order to create more space for larger ones. High thinning removes large trees, but also smaller trees that are in poor condition or overshadowed. Trees that are almost the size required for logwood are left to grow for the next 10–20 years.

Quality thinning removes trees overshadowed by larger ones, which are often small and very thin, or even larger ones not of sufficient quality.

A first thinning is usually carried out as low or quality thinning. When the forest is older, the most usual method is quality or high thinning.

A mature stand may also be thinned in what may be called spacemaking. In a mature stand, the largest trees have reached log dimensions and their rate of growth begins to decrease. Another possibility would be a regeneration felling, but if the forest owner wants to postpone this for financial, environmental or game management reasons, for example, spacemaking is an alternative.

In spacemaking, as many trees are removed as is possible without reaching the definition of a clearcutting, The aim is to achieve maximum natural regeneration.

Regeneration of small areas is identical with cultivation of small areas, except that the areas cleared are larger, 0.3–1 hectares. A new stand must be established after harvesting, unless it is expected to germinate naturally from the seeds of surrounding trees.

20–25 percent of the trees are removed. The site may be logged again when the new stand reaches the height of 2–4 metres. The goal is a mosaic-like forest structure.

Clearcutting with extra retention trees leaves more retention trees than a regular clearcutting. According to the Metsähallitus guideline, the volume of retention trees in this method should exceed 20 cubic metres per hectare or 15 percent of the harvesting area.

The article is based on an interview with Lauri Karvonen, Chief of Planning at Metsähallitus.

Read more from forest.fi: Believe it or not – ten amazing facts about mechanized timber harvesting