Limestone-biochar filtration reduces acidity – a new method for saving small water bodies

In Finland’s commercial forests, nature management has become a natural part of daily forestry work. New approaches are being developed to restore small water bodies in ways that support both healthy ecosystems and sustainable timber production.

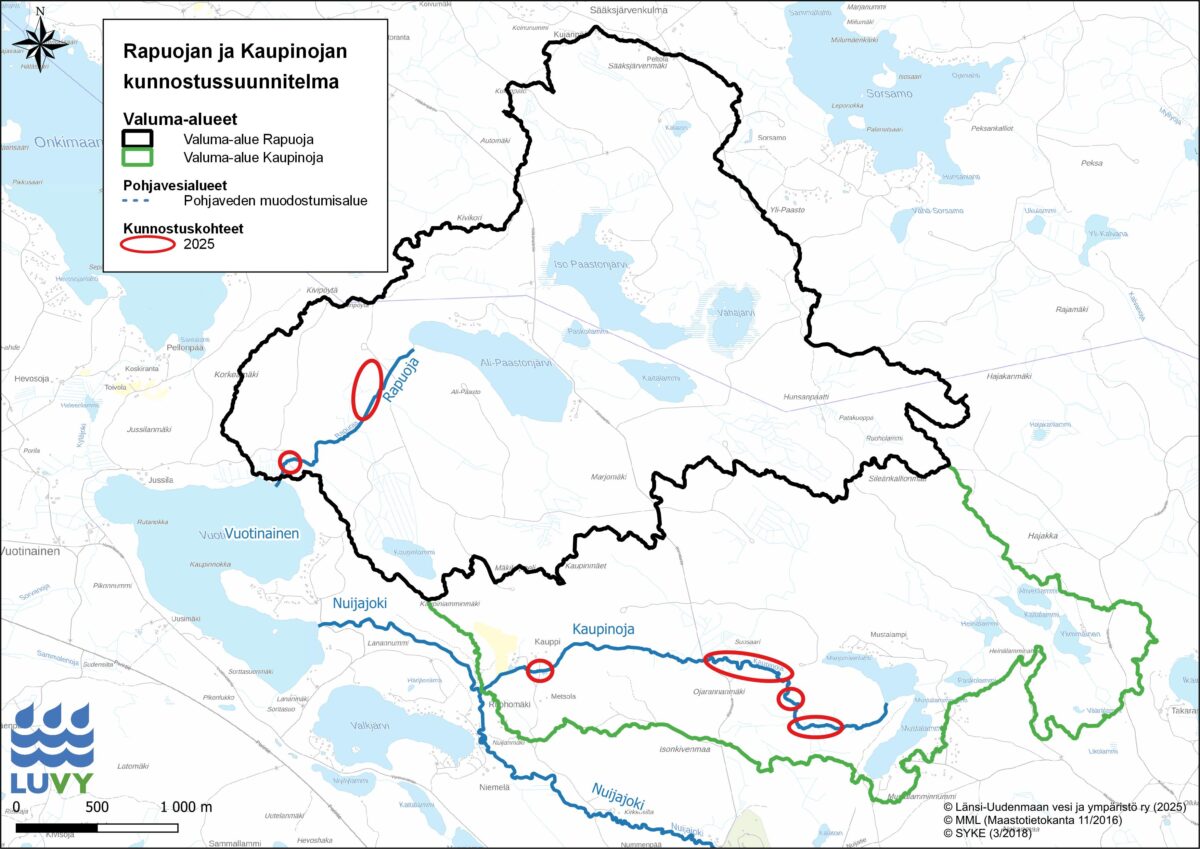

One of today’s most promising ecological restoration projects is unfolding in the Nuijajoki river basin near Karkkila, a small town about 60 kilometres northwest of Helsinki. In this pilot initiative, the Association for Water and Environment of Western Uusimaa (LUVY) is trialling a unique limestone-biochar filtration system designed to tackle acidic runoff from nearby peatlands. This innovative method aims to neutralize harmful acidity in stream water, especially after heavy rains, while supporting the recovery of sensitive aquatic life.

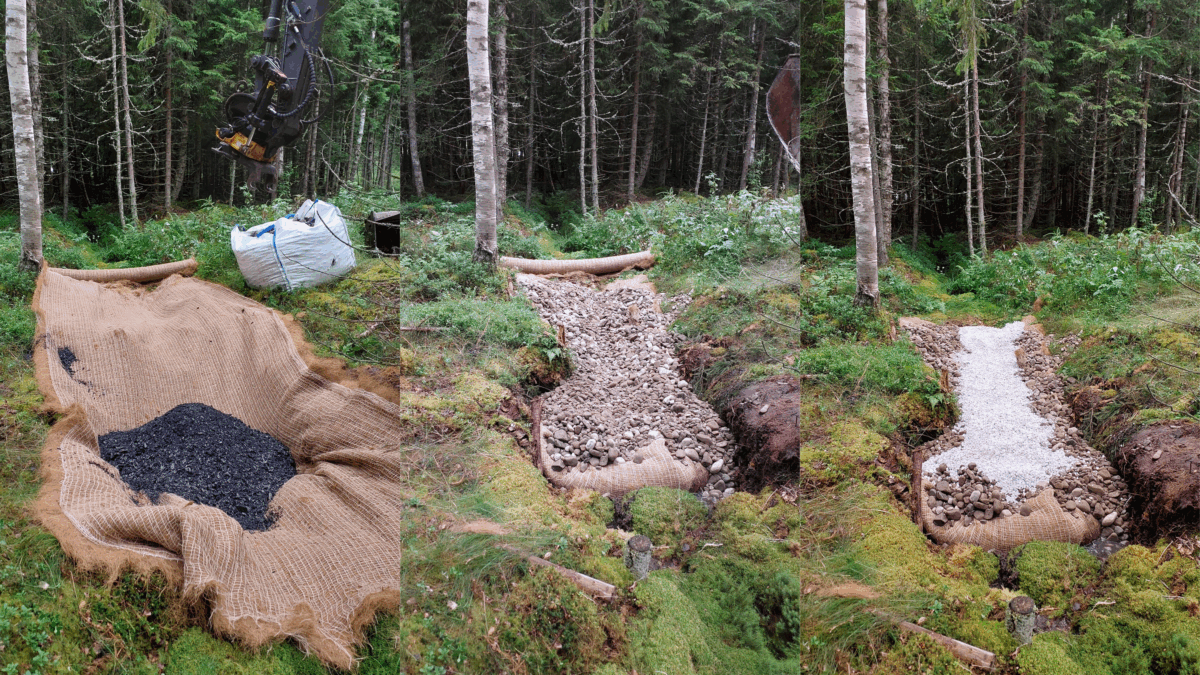

The innovative method is currently undergoing trials on land owned by the forestry company UPM. It is the first experiment of its kind in Finland, with no known comparable trials conducted elsewhere either, blending natural materials with smart water management to improve stream health.

“Stream-dwelling species like trout are especially vulnerable to overly acidic water and sudden changes in pH levels. In spring 2025, following heavy rainfall, the pH in the Kaupinoja stream in Karkkila dropped to as low as 4—a level considered highly acidic,” explains Mikko Melasniemi, a project worker at LUVY.

The filtration structures developed by LUVY aim to increase the pH of the water and reduce fluctuations in acidity. Although testing of the system is still in its early stages, initial results are encouraging. Since the structures were installed in July 2025, the water in Kaupinoja has maintained a more stable pH of around 6. Additionally, the flow slows down in the ditches before entering the broader water system, helping to buffer and regulate water quality more effectively.

“We’re tracking the results through continuous monitoring, and the autumn rains will be the first real challenge for the filtration structures,” says Juha-Pekka Vähä, head of LUVY’s freshwater team. “The data will help us assess how well the method works and guide future improvements.”

“Our hope is that these filtration systems won’t just stop small water bodies from becoming acidic—they’ll also inspire the forestry sector to explore new water protection techniques and adopt effective practices in their restoration efforts,” Vähä continues.

Cooperation for practical environmental restoration work

The limestone filtration experiment in the Nuijajoki river basin is more than a technical test—it is a powerful example of collaborative environmental action. It is part of the larger initiative titled Metsäluontomme helmet – Yhdessä pienten puolella (“Gems of our forest nature – Together for the small ones”), which focuses on protecting small but ecologically important water bodies in forested areas.

This project brings together the forestry company UPM, the Finnish Freshwater Foundation, and key funders including the Finnish Forest Foundation and Partioaitta’s Environmental Bonus—a nature-focused funding programme run by the Finnish outdoor retailer Partioaitta. By pooling resources and expertise, these partners are working toward a shared goal: restoring small streams and water bodies in forest landscapes to support both biodiversity and sustainable forestry.

“The project is a great example of the kind of cooperation biodiversity work requires,” says Martta Fredrikson, CEO of the Finnish Forest Foundation. “It’s vital to identify best practices and scalable solutions for improving the health of small water bodies in forested areas. The impact goes far beyond any single project.”

The aim is to ensure that ecological restoration and small water body rehabilitation are not isolated measures, but a natural part of everyday forest management – just like soil preparation or seedling stand management. New legislative obligations are also driving this change in thinking.

EU restoration regulation is changing the rules of the game

The importance of restoring small water bodies—like streams, springs, and ponds—has gained significant attention in recent years, both across Europe and within Finland. These ecosystems are often impacted by forestry activities, and their health directly influences water quality and the diversity of aquatic life.

Under the EU’s updated restoration regulation, member states are now required to rehabilitate at least 20 per cent of their land and water areas by 2030. By 2050, all degraded ecosystems must be included in national restoration efforts. In response, Finland is currently drafting its own restoration plan, set to be finalized by August 2026. One of its central goals is to improve the condition of small water bodies.

“Small water bodies are vital ecosystems that shape the health of their surroundings,” explains Vilma Kaukavuori, an expert at the Finnish Freshwater Foundation. “Restoring them is a powerful way to boost biodiversity and enhance water quality.”

Nature and the economy side by side

From UPM’s perspective, ecological restoration does not threaten wood supply, it supports it. Much of the restoration work takes place in areas where forestry is not economically viable, such as drained peatlands with poor tree growth.

“When natural values are high and forestry potential is low, restoration becomes a smart solution,” explains Miika Laihonen, Senior Specialist in Nature Management at UPM.

He emphasizes that boosting biodiversity in commercial forests strengthens their overall health.

“While we often refer to this work as nature management rather than restoration, the aim is the same: to improve ecological conditions and increase biodiversity. Sustainable forestry is about finding the right balance between production and protection. It’s a matter of coordinating multiple goals—and it is absolutely achievable.”

Laihonen also points out that restoration can unlock new business opportunities alongside traditional forestry, such as offering nature management services or participating in environmental compensation markets.

“Enhancing the natural environment is an important part of responsible forest asset management, and environmental restoration is an integral part of that process,” he says.

“It also holds potential for complementary business opportunities alongside forestry, so it’s a topic worth keeping an eye on.”

Cooperation for more effective restoration

UPM tracks the impact of its restoration efforts through both visual observation and scientific collaboration. As nature takes time to recover, results often emerge only after several years. Still, early signs are encouraging: trout have been spotted in electrofishing surveys following stream restoration, and species that rely on decaying wood are becoming more common in several areas.

Looking ahead, UPM plans to focus its restoration work more strategically, targeting entire catchment areas and strengthening ecological networks. Developing better methods is also a priority to identify what works best.

“We’re very optimistic about the limestone–activated carbon structures developed by LUVY,” says UPM’s Miika Laihonen.

“Our partnership with LUVY on this filtration method shows how new solutions can emerge through collaboration.”

While more data is needed to confirm the method’s effectiveness, the Finnish Freshwater Foundation sees strong potential.

“We don’t yet have enough information about the filters, but they’re promising experiments worth close attention,” says Vilma Kaukavuori of the Foundation. “It’s important that pilot projects like this happen—and UPM has made that possible.”

If successful, the method could be scaled up not only across Finland, but also in other countries facing similar challenges with acidic runoff and forest-related water impacts.

As Kaukavuori notes: “The best solutions are those that become standard practice. That’s how we’ll reduce the environmental pressure from forestry and climate change. Forest companies can lead the way, setting examples that private landowners can follow with confidence.”