Decaying wood in Finnish forests increases rapidly – biodiversity and harvesting can be harmonized

The amount of decaying wood in Finnish forests is able to increase to 20 cubic metres per hectare by 2065, even with harvesting levels higher than today. This is not as much as in unmanaged forests, but it may well be sufficient in terms of biodiversity.

The preservation of structural features important for Finnish forest nature – such as the amount of decaying wood and large and old trees – was studied by means of scenarios based on different levels of harvesting and nature management as part of the Forest Environment Programme of the Finnish Forest Industries Federation.

The increase of dead, usable wood – in other words, wood that could be used for fuel at least – is more or less on the same level in the scenarios studied by Natural Resources Institute Finland: for an annual harvesting level of 70 million cubic metres and for the highest sustainable level.

A seminar presenting the outcomes of the programme also revealed that the level of nature management did not affect this result significantly. This is important, because the lack of decaying wood is one of the greatest biodiversity problems in Finnish forests.

The amount of decaying wood increased in all scenarios from the current figure of three to nearly 20 cubic metres per hectare. According to statements by several biodiversity experts, this could be sufficient to safeguard the dynamics found in natural forests, although the actual amount of decaying wood in them is much larger.

Number of stout broadleaves also increases

The number of stout broadleaves is also important for forest biodiversity, and in all scenarios it will increase significantly by 2065. This is most important with regard to stout aspen, the most important tree species for the biodiversity of Finnish forests. Its amount has increased sixfold since 1980 and continues to increase.

However, the amount of aspen is only increasing in commercial forests. ’The problem is that aspen is not able to regenerate in protected forests,’ says Kari. T. Korhonen, Principal Scientist at Natural Resources Institute Finland.

The reason became clear from the reply given by Kimmo Syrjänen, Head of Unit at the Finnish Environment Institute, when asked whether the rules for hunting in protection areas should be changed: ’Yes, they should. Shoot the elk,’ said Syrjänen, referring to the fact that the root sprouts of aspen are favoured by elk.

The significance of retention trees can be illustrated by the fact that their share of all stout broadleaves in Finnish forests, protection areas included, may be close to 70–80 percent. ‘Their share of the total timber stock could increase from the current 1.4 percent even up to 3.6–8.5 percent by 2065,’ said Olli Salminen, Senior Research Scientist at Natural Resources Institute Finland, presenting the scenarios at the seminar.

This might be as high as it can get. ‘By now in Finland, biodiversity has been part of forestry guidelines for 25 years. During that period the amount of decaying wood has increased in commercial forests, but the process cannot be speeded up. Wood takes its time to decay, no matter what we do,’ said Lea Jylhä, Forest Specialist at the Finnish forest owners’ union MTK.

Current harvesting levels are not excessive for nature

The scenarios studied show that even if nature management is intensified, harvesting could be sustainably kept at the current level – 78 million cubic metres annually – until 2024, after which it could be increased to 87 million. With the current intensity of nature management, the harvesting level could be higher: 86 million cubic metres to start with, and in 2065 it could be increased to 92.5 million.

The past development of structural features important for forest biodiversity was studied with data from the National Forest Inventories. The current status was compared with data from 1980.

The number of retention trees and broadleaves on clearcut sites started to increase soon after forest certification was introduced at the end of the 1990s. The increase has been significant.

’On the other hand, old forests over 120 years of age have decreased in southern Finland in the 2000s, and their area is now the same as in 1980. In northern Finland, the area of old forests, that is, forests older than 160 years is no longer decreasing,’ says Korhonen.

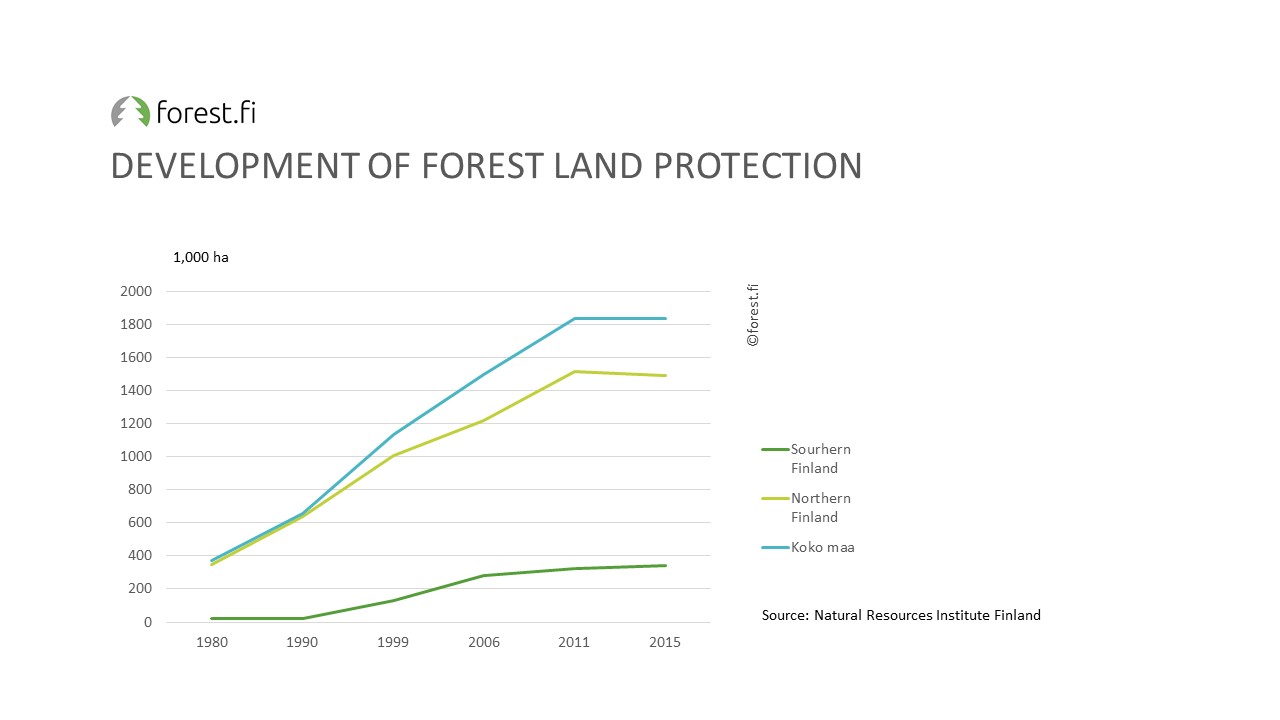

The share of protected forests of productive forest land in northern Finland has increased fivefold and in southern Finland up to 17-fold. The average volume of timber stock per hectare has increased by 40 percent – in less than 40 years.

Forest Environment Programme adopted permanently

The effects of nature management on epiphytes was also studied. Epiphytes are plants or fungi growing on other plants. Epiphytes are indicator species: their presence or absence indicates the state of the natural environment.

’Not all epiphytes are endangered by any means. Two examples of epiphytes are beard mosses and lichens,’ says Syrjänen.

The significance of protected key biotopes, protection areas and retention trees was studied with a literature survey. According to Syrjänen, key biotopes are good environments for lichens and mosses, but it is debatable whether they are able to move from one site to another.

’As such, these species spread easily if they just have somewhere to go. They might perhaps be helped by surrounding protected key biotopes with zones where only lighter forestry methods are carried on,’ says Syrjänen.

Retention trees, on the other hand, provide little protection to epiphytes immediately after harvesting. ’Still, epiphytes start to recover, sometimes in five, but at the latest in 30 years after a clearcut,’ says Syrjänen.

According to Syrjänen, aspen is important for lichens, as is old hardwood and dead wood. The number of retention trees should therefore be increased in connection with fellings not classified as regeneration, and they should be left in groups rather than singly – both of which are already an increasing practice in Finnish forests.

’Also, the regeneration of aspen in protection areas should be ensured,’ says Syrjänen.

All in all, the study shows that nature management efforts are appropriate and effective. In consequence, the Finnish Forest Industries Federation has decided to adopt permanently the Forest Forest Environment Programme, originally scheduled to end in 2020. Its future contents are now being planned.