Natural resource planning makes use of ideas generated by stakeholders: ”Could serve as an example for others”

Thirty stakeholder groups participated in the use of state-owned lands and waters in Ostrobothnia, western Finland. Participants at the planning meeting considered that Metsähallitus is a pioneer of open cooperation and could serve as an example to others.

An owl is flying about in the meeting room in Nallikari, Oulu. About thirty influential people from Ostrobothnia and almost as many Metsähallitus employees are tossing the soft toy around.

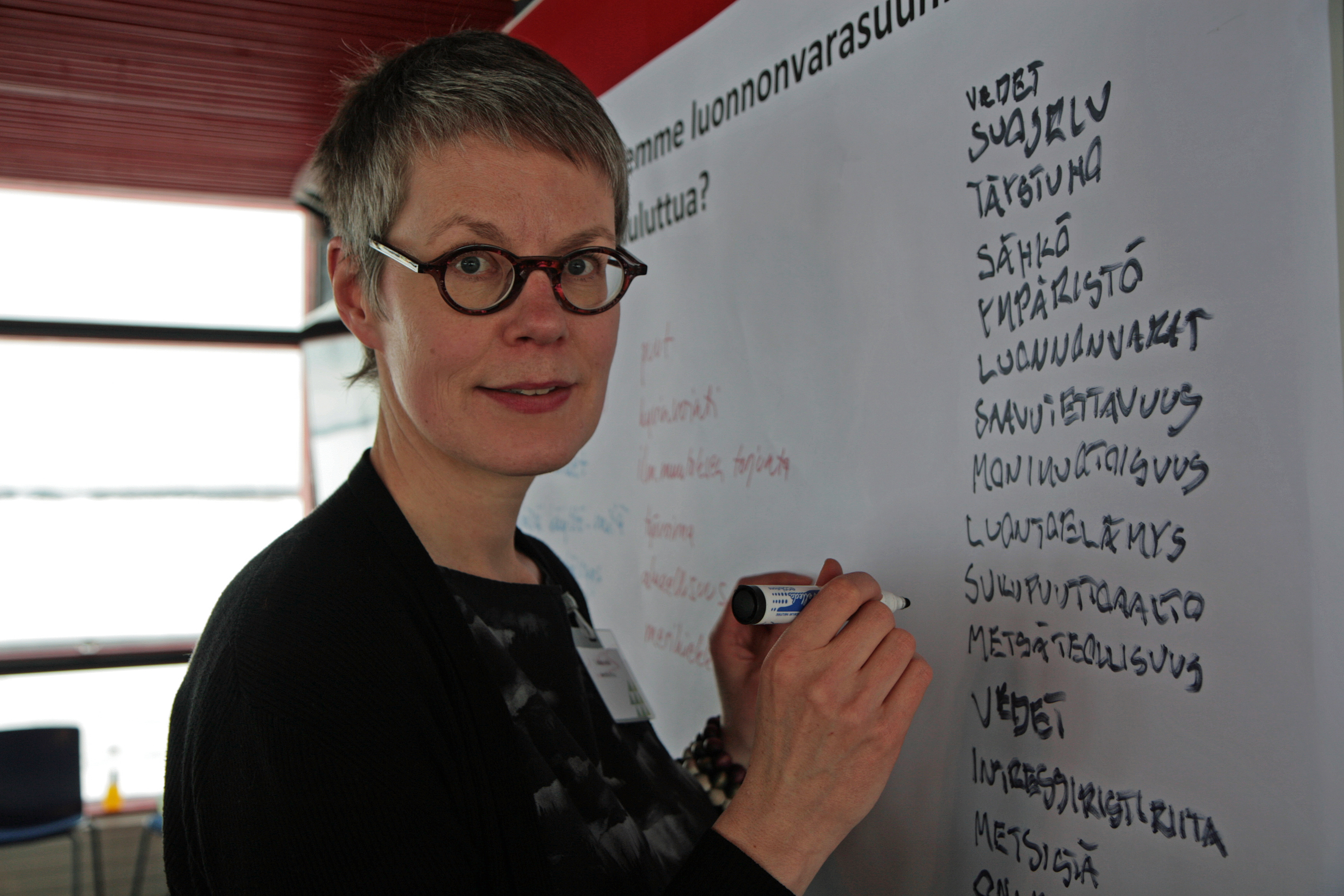

As soon as you catch the owl you are allowed to speak one word. The idea is to speculate on what is going to be talked about in natural resource planning in five years, and the list of words is long: nature experiences, accessibility, wave of extinction, happiness, electricity, diversity, forest industry.

The participants of this early-morning exercise are now meeting for what is their third and final day. Their task is to draft a natural resource plan for Ostrobothnia. The plan will steer the use of state-owned lands and waters in the regions of Central and Northern Ostrobothnia for the next five years.

”The natural resource plan could also be called Metsähallitus’ action programme for the planning period and the regions concerned,” says Johanna Leinonen, who chairs the project steering group. ”Stakeholder cooperation ensures that it contains a strong local vision and local experience.”

Reconciling different interests is the key

In Finnish debate on the use of forest the focus often lies on the state-owned forests, managed by Metsähallitus. They cover a third of the land and water area of Finland and are the common property of everyone, particularly with regard to recreation, nature conservation and nature tourism.

In the opening words of its recent press release, Metsähallitus noted that reconciling the wishes and needs of stakeholders is a requirement for its success. In fact, Metsähallitus is known in Finland as one of the pioneers of participatory activity. It makes use of stakeholder cooperation not just in the drafting of extensive regional natural resource plans, but also in other projects related to land use.

”We have a genuine desire to make everyone’s voice heard,” says Pentti Hyttinen, Director General of Metsähallitus, who is present in Oulu to meet the participants of the natural resource planning workshop.

The Ostrobothnia cooperation group includes representatives from almost thirty associations, educational and research organisations, companies and official bodies. In addition, a separate workshop has been organised for young people, and participation through a web survey has been open to anyone interested.

”Natural resource planning and stakeholder cooperation have an extensive effect on Metsähallitus’ activities. Stability is created precisely because there is a shared understanding of what should be done with forests, for example,” notes Hyttinen.

”You really manage all this?”

Natural resource plans are drafted every five years for Southern Finland, Ostrobothnia, Kainuu, Lapland and Upper Lapland. In Ostrobothnia, the natural resource planning covers about one third of the area; this includes 910,000 hectares of forest and 738,000 hectares of sea and inland waters.

”The state owns a lot of land in Ostrobothnia, and this has increased interest in natural resource planning, especially among local authorities. The planning includes many organisations that we have cooperated with for quite a long time,” says Project Manager Tuulikki Halla. Photo: Anna Kauppi

”It is always good to be able to exchange information and ideas, and that is something you can do within stakeholder cooperation, and not just with Metsähallitus, but also with other stakeholders. Discussion during the workshops is open, and what we record on the sheets is OK. On the other hand, as regards matters out in the field and how things are put into practice, Metsähallitus often ignores the views of others,” says Anne Ollila, Director of the Reindeer Herders’ Association. Photo: Anna Kauppi

This time, the guidelines for Ostrobothnia have been worked on since last autumn. For many of the participants this is not the first time that they are involved. Though the process is lengthy and familiar, the participants are still amazed at the enormous number of responsibilities that Metsähallitus has.

Each stakeholder representative has been challenged to produce ideas for all guidelines, which include mitigation of climate change, profitability of forestry, waterways conservation solutions, management of protection sites and protection of cultural heritage, among others. In addition to forestry and biodiversity, the discussions have concerned recreational use and tourism, hunting and fishing economy, real estate business and wind power stations. Other topics have included the future use of sand from the seabed and leasing plots for data centres, for instance.

During the workshop, Metsähallitus employees provide brief information spots on both new and familiar themes, such as virtual planning of forest management or Metsähallitus’ actions to support the health-promoting aspects of nature.

Many of the representatives say that they have gained a new understanding of not just Metsähallitus’ operations and their scope, but also of the goals of other stakeholders. Anne Ollila, Director of the Reindeer Herders’ Association, also praises the openness of discussion, despite feeling that not nearly everything they record in writing here will be implemented in reality.

”We can see that we’re being listened to”

Stakeholder cooperation in natural resource planning was started in the 1990s, as debate on the responsible use of natural resources grew stronger. To begin with, stakeholder discussions were dominated by topics such as the importance of forests for employment, and meetings were taken up by attempts to arrive at a common compromise on harvesting volumes.

These days, participation is more in the nature of innovative generation of ideas, with the aim of looking towards the future.”Metsähallitus is a pioneer, and the methods it uses could very well be adopted in other sectors of society,” says Teemu Junttila, civil engineer employed by the town of Kuusamo, and continues that he is impressed by the methods used in the workshop.

One of the old-timers among stakeholder representatives is Merja Ylönen, Chief of the Northern Ostrobothnia District of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation. She has plenty of experience of cooperation with the Parks and Wildlife unit of Metsähallitus and is of the opinion that the cooperation methods have improved over time; she has also participated in cooperation projects where the terms were dictated by Metsähallitus.

”During this round of natural resource planning you can make your thoughts count as long as you have the persistence to voice your comments,” Ylönen says. ”Looking at the guidelines, you can also see that we’ve been listened to.”

Ideas are taken forward

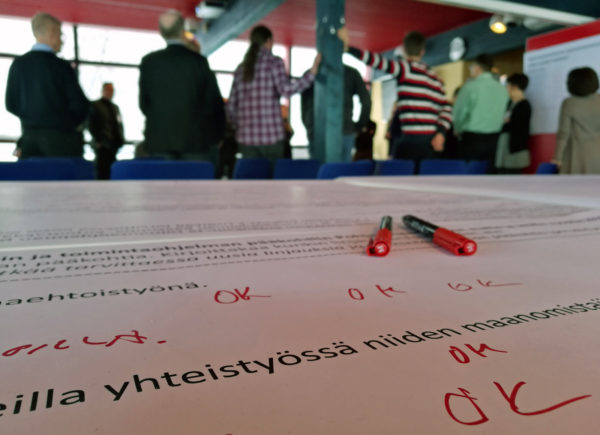

The guidelines are recorded on large paper sheets spread on the meeting table. At the first meeting, the participants literally faced a blank table, but by now the sheets contain practically finalized guidelines and measures which the members of Metsähallitus’ steering group have formulated on the basis of ideas and opinions from the stakeholders.

Now, at the third meeting, the participants can comment on the guidelines one more time. For the most part, notations on the sheets are endorsed with OK’s. Some things are rephrased or further specified. More attention must be paid to flood control, and someone wants a better management of introduced animal and plant species.

During the final discussion the owl is again tossed about, but this time catching it means you can ask a question. Many people express doubts about Metsähallitus’ ability to implement everything that has been hatched here.

”All of this will be taken forward,” Leinonen assures. ”Responsibility for the guidelines is divided between many experts and operational units, and a lot of this is already part of our customary operations and of how we develop them.”

The natural resource plan for Ostrobothnia will be finalized by May. After that, another cooperation group will be established for Lapland to start natural resource planning there.

Metsähallitus: Land-use planning