From forest legacy to future food: Finland converts industrial sidestreams into sustainable protein

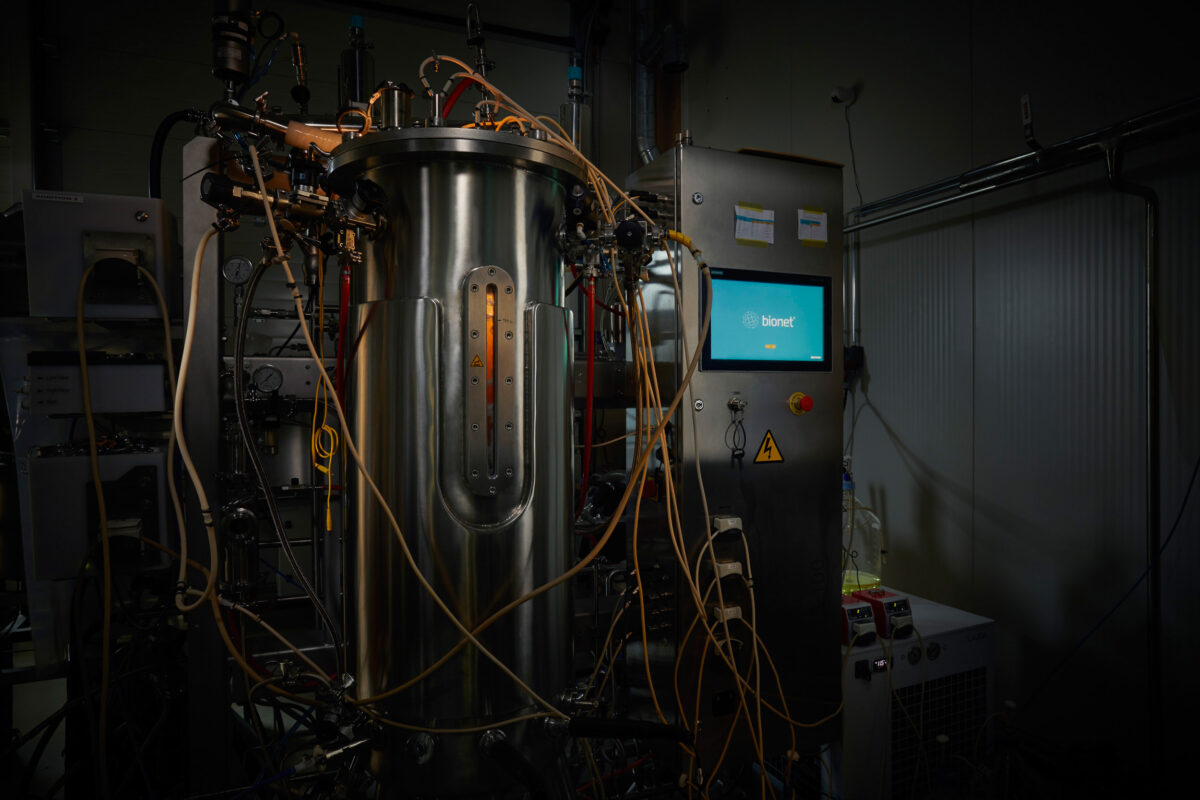

The world’s first factory producing food‑grade Pekilo fungal protein is taking shape in Kantvik, a coastal village in Kirkkonummi—just 36 kilometers west of Helsinki. Designed to harness industrial sidestreams, the plant represents the revival of a Finnish innovation with roots deeply embedded in the nation’s forest industry.

At the forefront of this development is Enifer, a biotechnology company spun out of VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. Enifer is reviving the Pekilo fermentation process, first pioneered in the 1960s, which cultivates fungal mycelium as a source of high‑quality protein. While the method has been modernized to meet today’s food safety and hygiene standards, its core principle remains unchanged: turning industrial sidestreams into sustainable nutrition.

The origins of Pekilo lie in the 1960s, a decade marked by global food insecurity. In that era of scarcity, Finnish researchers devised a groundbreaking solution—fermenting pulp mill sidestreams into protein feed. This innovation became a milestone in Finland’s bioindustrial history. Now, decades later, Pekilo has resurfaced to face a new global challenge: sustainability.

Unlike its original mission to combat famine, today’s return of Pekilo is driven by the urgent need to reduce the environmental footprint of food production. As climate change, resource constraints, and ecological pressures strain traditional protein sources, Pekilo offers a circular alternative. By converting existing sidestreams into protein without adding new burdens to the environment, Finnish bioinnovation is once again answering the call of its time—first famine, now sustainability.

“Up to a third of global emissions come from food production,” notes Simo Ellilä, CEO of Enifer. “If we want to curb greenhouse gas emissions, we need a lot of innovations in this sector”

A sustainable protein source

PEKILO® isa high‑quality protein produced by fermenting fungal mycelium (the mass of thread-like structures through which fungi absorb nutrition). It offers a sustainable alternative to both plant‑ and animal‑based proteins.

Today, instead of pulp mill waste, the production process of Pekilo relies on clean, traceable sidestreams, such as lactose‑rich liquids from dairies. Yet the legacy of Finland’s forest industry research remains embedded in the innovation, linking past bioindustrial ingenuity with present‑day sustainability needs.

“The energy efficiency and operational reliability of the PEKILO® mycoprotein production process have been extensively studied, which gives us a strong foundation,” explains Ellilä. “What brings new value today is production aimed at food quality—setting strict requirements for both hygiene and traceability.”

An innovation born by chance

In 1963, at the Central Laboratory of the Paper and Pulp Industry (KCL) in Espoo, Finland, biochemist Otto Gadd made a discovery that reshaped how industrial sidestreams were perceived. He observed that the Aspergillus niger fungus thrived in sulphite waste liquor—a by‑product of paper manufacturing. This sparked a radical idea: could protein be cultivated from the forest industry’s waste streams?

By the 1970s, the idea had progressed from a laboratory curiosity to full‑scale industrial production. Plants run by Tampella in Jämsänkoski and Mänttä began manufacturing Pekilo as animal feed.

The product was notable for its high protein content, low fat, and neutral taste—qualities that made it versatile even at the time.

By the early 1990s, however, changes in the pulp and paper industry disrupted production of the fungal protein. Finnish mills phased out the sulphite process in favor of the kraft (sulphate) process, which produced stronger, more versatile pulp and proved economically superior. As kraft became the global standard, sulphite liquor sidestreams disappeared.

With no suitable raw material available, production of PEKILO® feed ended in 1991. The fungal strain itself was not discarded, but was preserved in VTT’s Culture Collection, stored at –80°C. There it remained for nearly three decades—effectively in hibernation—until renewed interest in sustainable proteins led Enifer to revive the process.

“Not just a new source of protein”

As the world’s population grows, so too does the demand for protein. By harnessing existing industrial sidestreams, Pekilo stands out as a potential game‑changer in the search for climate‑friendly food solutions. The product itself contains 50–70% protein, is almost fat‑free, and has a neutral taste—making it highly versatile. Beyond animal feed, it can be used in baking, meat substitutes, and other food applications.

The Pekilo plant under construction in Kantvik will have a capacity of 500 kilograms per hour, translating to three million kilograms of protein annually. That’s enough to feed 40,000 people if it were their sole protein source, the company estimates.

In its first phase, production will supply the European pet food industry, but Enifer’s ambitions extend far beyond.

“PEKILO® protein is not just a new source of protein; we want it to be on a par with animal‑based and plant‑based proteins in all applications,” says CEO Simo Ellilä.

“Expansion into the food market will begin as soon as legislation allows. Approval has already been granted in the US, and we expect Europe to follow within a few years.”

Eyes on Europe and America

Construction is progressing well inside the Suomen Sokeri (part of the Sucros Group) factory wing. The first equipment will be commissioned in early 2026, with full capacity expected by year’s end, Ellilä says.

“The walls are old, but everything inside is new. This allows us to utilise existing infrastructure and optimise investment costs,” explains Mia Horttanainen, Enifer’s COO.

The Kantvik facility will operate as a continuous fermentation process, where uninterrupted production is critical.

“The process cannot be stopped for long. If downtime exceeds a few hours, the fungal mycelium deteriorates, forcing a full restart,” Horttanainen notes.

Although automation will be advanced, human oversight remains central.

“Not everything can be left to automation and AI. We take samples, examine them under a microscope, and monitor growth. Human vigilance ensures quality and safety,” she adds.

At its core, the plant embodies the circular economy: “What is waste for one industry becomes raw material for another. This is vital for nature,” Horttanainen emphasizes.

Meanwhile Simo Ellilä sees Kantvik as only the beginning:

“Next, we plan to build larger facilities in Europe and America. The investment decision for the next plant will be made within a year.”